Lynn Visson was a UN interpreter during the height of the Cold War. She can still rattle off grandiose Soviet titles like it was yesterday.

“General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party — you had that practically memorized,” Visson recalls.

After 23 years, she’s still at it, interpreting from French and Russian into English. She’s witnessed — and spoken for — some pretty heavy hitters. “I remember Castro spoke for all of eight minutes, but the charisma was incredible,” Visson says. “The electricity the man generated — Bill Clinton could do that, too, Gorbachev could do that. Some other delegates were great speakers, but they didn’t light that spark.”

These days, we’re long used to seeing diplomats at the UN plugged into earphones, listening to speeches that are instantaneously translated into one of the six official UN lanugages — English, French, Arabic, Chinese, Spanish and Russian, but simultaneous interpretation is actually a rather recent invention, developed in 1945 for a very different global event: the Nuremberg Trials.

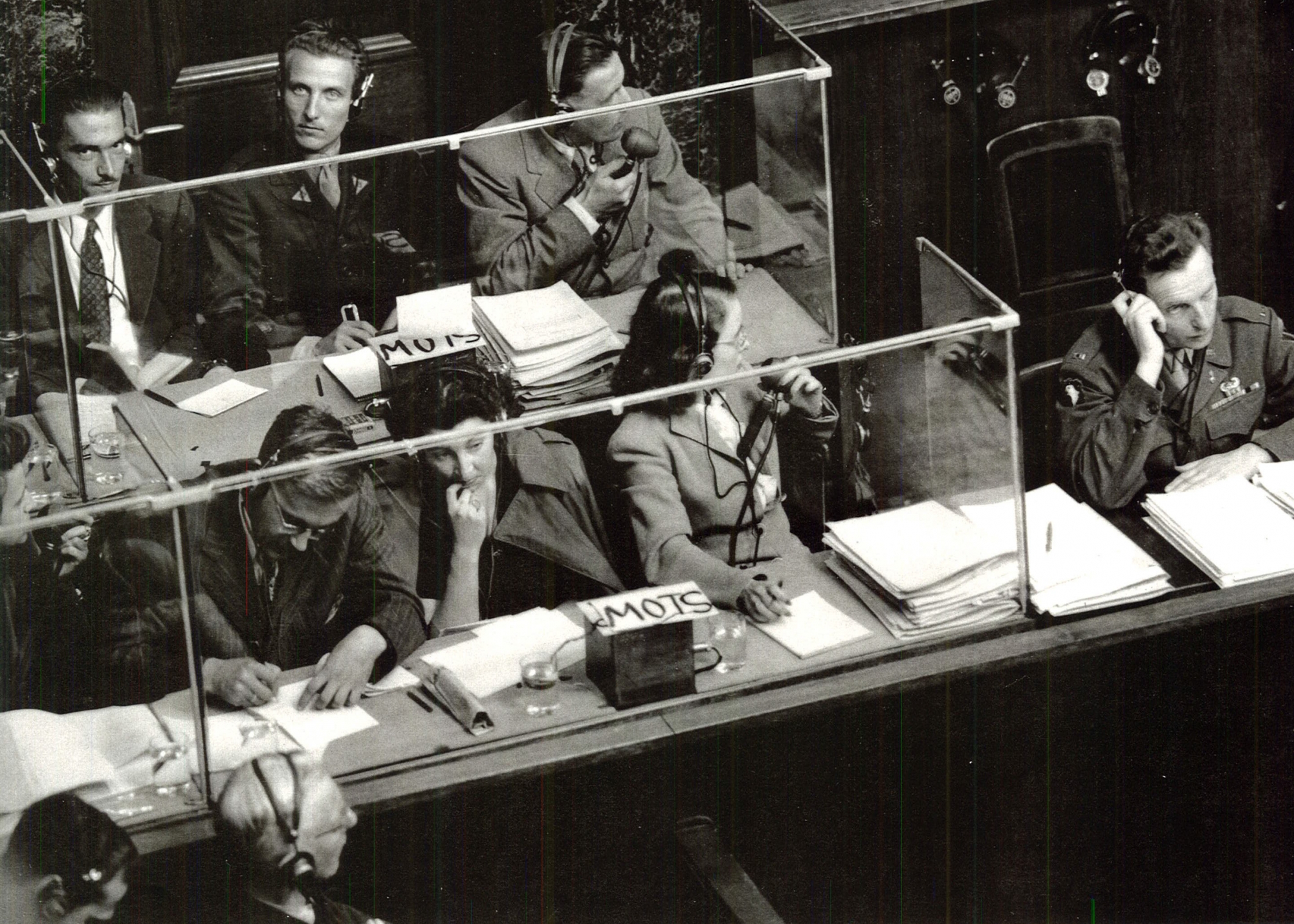

(From left, Capt. Macintosh of the British Army translates from French into English, while Margot Bortlin translates from German into English and Lt. Ernest Peter Uiberall monitors the translations at the Nuremberg trials after World War II. Photo Credit: Francesca Gaiba)

Before the Nuremberg Trials, any kind of interpretation was done consecutively — talk first, and then wait for the interpreter to translate. But at the end of World War II, the Allies created the International Military Tribunal, which was charged with an explicit mission: “fair and expeditious trials” of accused Nazi war criminals.

“Those two words put enormous constraints on the people organizing the trial,” says interpreter and historian Francesca Gaiba, who has studied the origins of simultaneous interpretation at the Nuremberg Trials.

She says holding a trial that was “fair” and “expeditious” meant speeding up translations of the four languages of the nations involved: English, German, Russian and French. The solution was thought up by Col. Leon Dostert. Born in France and a native French speaker, Dostert became an American citizen and a foreign language expert for the US Army.

“He was the person who thought it was possible for a human being to listen and speak at the same time,” Visson says.

Possible, yes, but far from easy. And then there was the problem of transmitting all of those languages in real time. This was 1945, so digital recordings and tapes weren’t around. But Dostert pressed on and consulted with IBM to develop a system of microphones and headsets to transmit the cacophony of languages. He hired interpreters and practiced this new type of interpreting with them.

And somehow, despite a few episodes of tripping over cords in the courtroom, Dostert’s system worked.

(Interpreters at the Nuremberg Trial; Front: English desk; Back: French desk. To the left, monitor. Photo Credit: Francesca Gaiba)

Even before the Nuremberg trials were over, Dostert had taken his system to the UN in New York. It’s still the model being used today, albeit with some minor upgrades in technology.

“When I started, all interpreters were lugging around heavy dictionaries,” Visson remembers. “Now they’re lugging around iPads and notebook computers because most glossaries are in those.” She says TV monitors in the back booths also let interpreters watch the expressions of diplomats and the movements of their mouths.

But technology still hasn’t advanced enough to replace the interpreters themselves. “The computer can’t pick up the intonation,” Visson says.

But one of the biggest challenges for interpreters is often not the tone, but simply figuring out what a diplomat is saying.

“People with foreign accents for example, you want to be careful that when you hear somebody saying, ‘Mr. Chairman, we wish to congratulate you on your defective leadership.’ You know he didn’t mean his ‘defective leadership,’ he meant his ‘effective leadership.’” Visson says. “But you’ve got to not be simply auto-translating word for word, because heaven help you if you say we congratulate you on your defective leadership.”

Of course, relaying the words of world leaders also means not mincing them, be they Holocaust denials, carefully crafted insults or strongly worded Cold War rhetoric.

“One of the things you are taught is that you’re like an actor on stage,” Visson says. “There are plenty of actors who play the part of people who are absolutely vile. So I think if you look on it as acting, it can almost become fun — even if you are saying things that you personally find repugnant or hateful.”

Reporter Nina Porzucki