Before delving into the complex practice of translation, consider sparing some time discovering its beginnings.

By Abdellah Erraji, Morocco World News

Rabat – Translation is much more ancient than one can imagine. For a practice to transform into a discipline can take thousands of years to develop. Since history covers an expanded series of events, one cannot mention the entire history of translation in just a few lines. The aim of the present article is to offer a glimpse into translation history throughout three major periods, namely the age of antiquity, the Islamic age, and the age of enlightenment.

Translation in the age of antiquity

Everything began in about 3000 BC when the earliest piece of translation appeared as an epic “The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh.” Interpreters translated the epic into roughly five Asiatic languages, and played a crucial role in servicing the empires of that time, most importantly Persia and Greece.

The “Septuagint” is the first Greek Old Testament ever translated from the original Hebrew by 70 Hebrew scholars who conveyed the meanings thought-for-thought rather than word-for-word.

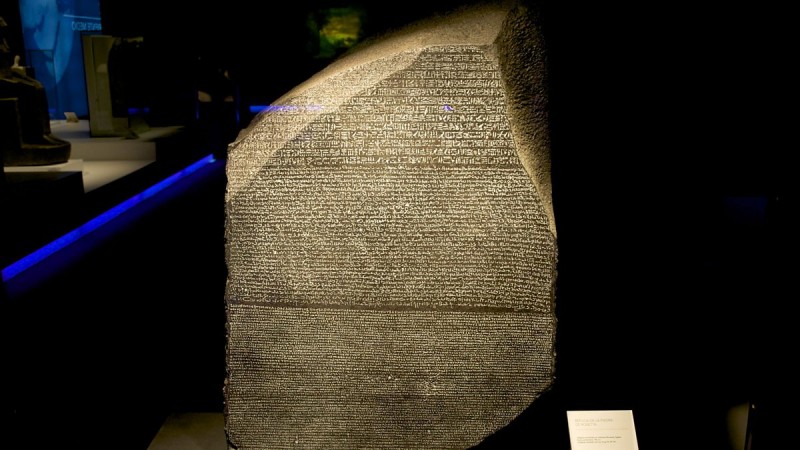

The Rosetta Stone, currently found at the British Museum, is another cornerstone of the beginnings of translation. Dating back to 196 BC, the stone has three equivalent scripts carved into it. The first two scripts are in Ancient Egyptian and the third in Ancient Greek.

Between 195 BC and 420 AD, scholars such as Cicero, Horace, Terence, and Saint Jerome had a say in translation.

Cicero, who is a Roman Statesman, a lawyer, a scholar, and a writer, declared: “I did not translate as an interpreter, but as an orator, keeping the same ideas and forms, … or figures of thought, but in a language which conforms to our usage. And in doing so, I did not hold it necessary to render word-for-word, but I preserve the general style and the force of language.”

Horace, known as a satirist and a translator, sets the goal of translation on “producing the aesthetically pleasing and creative text in the target language (TL).”

Terence, a Roman playwright, describes the translator’s role as “a bridge for carrying across values between cultures.”

Saint Jerome, Secretary to the Pope, produces the Latin version of the Bible known today as “Vulgate.” The term “sense-for-sense” is up to now of Saint Jerome’s own coinage.

Translation in the Islamic age

Translation continued to develop until the Middle Ages (500-1500 AD), particularly in the Islamic State and under the control of different rulers. Prophet Muhammad -peace be upon him-570-632 AD) came to spread Islam and had to communicate with non-Arabic speaking communities such as the Jews and the Romans.

At that time, Zaid Ibnu Thabet (610-660 AD) performed an eminent role in translating inbound and outbound letters between the Prophet and the kings of Persia, Syria, Rome, and the Jews. Salman El Farisi (568-657 AD) is also one of the early translators of the Quran who translated its meanings for Persian Muslims.

The Umayyad’s reign extended from Europe to India between 661 and 750 AD, which began with the Caliph Omar bin Abd Alaziz. During his reign, Greek, Byzantine, Persian, and Egyptian books of medicine, chemistry, and mental subjects were translated into Arabic by Prince Khalid ibn Yazid and other translators.

Not until the establishment of the Abbasid sovereignty (750-1517 AD) did translation reach its peak. Caliph Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid Al Ma’moun marked the history of translation by founding “Bait Al Hikma” (The House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, Iraq. The institute was a milestone of translation that hosted scholars from India and Persia.

Al Kindi is one of its graduates as well as translators such as Abu Yahya Ibn al-Batriq and Hunayn Ibn Ishaq Al-Jawahiri. With his literal strategy, Ibn al-Batriq fathered the translation of ancient Greek texts into Arabic, whereas Ibn Ishaq Al-Jawahiri adopted the sense-for-sense strategy for a more fluent target language.

In his book “Kitab al-Hayawan,” Al-Jahiz came up with a complete theory of translation wherein he called the attention of the following: “The translator’s knowledge in the subject to be translated”, “the translator must be the most eloquent in both languages,” and “making a mistake in translating topics in religion can’t be tolerable.”

The time between the thirteenth and the end of the fifteenth century prioritized the sense-for-sense strategy, thus letting translation continue to bloom in the novel era of enlightenment.

Translation in the age of enlightenment

Amongst the outstanding figures of the enlightenment age, there is Martin Luther (1483-1546), a German priest, biblical scholar, and linguist. He sowed the seeds of translation procedures such as “changing” (switching the order of words), “addition” (adding modal auxiliaries), “retrenchment” (deletion of Greek or Hebrew terms with no equivalents in German), “expansion” (translating single words into phrases), and “simplification” (translating metaphors into plain language and vice versa).

French Humanist, painter, and scholar Etienne Dolet (1509-1546), believes that a translator must “comprehend, at first, the author’s intention and intent of the text,” refrain from the word-for-word strategy, use the parts of speech naturally as they should be, and generate an effect as natural as possible to the reader’s mind.”

English poet, dramatist, and literary critic John Dryden (1631-1700), proposes three procedures to be applied in any translation, namely the “metaphrase” which refers to the process of translating literally; starting with a word by word and line by line translation. Secondly, there is “paraphrase” when words are modified using the first procedure however more focus is placed on the meaning and sense.

The third procedure is “imitation” (translating both the sense and the lexicon to adapt them to the target culture).

German theologian and translator Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), believes there are two approaches when translating, “foreignization” which prioritizes the source text to bring the reader closer to the author’s culture, and “domestication” which makes the translation closer to the target text to draw the author closer to the reader’s culture.

Translation as a misunderstood discipline

Today, many people who have never been exposed to translation assume that it is simply the transformation of words from one language to their literal equivalents in another language, thus marking the completion of the task.

If they are assigned, for instance, this sentence to translate into Arabic “her humane behavior warmed my heart,” they would translate it as “إن سلوكها الإنساني أدفأ قلبي”. However, those who have already had the opportunity to study translation argue that translation is rather the transformation of words to their cultural equivalents.

Therefore, they would translate the sentence as “إن سلوكها الإنساني أثلج صدري” the back translation would be “her humane behavior freezed my chest.”

From a meteorological perspective, the western culture uses “warm” because it is geographically known for its comfortable temperature, and finding a source of warmth puts someone at ease. However, the climate in the Arab world is known for its high temperature, which makes the population long for the cool weather.

Translating is not converting words as single units but construing the culture they bear, the civilization they emanate from, and the entire system of rules they are governed by. Translation is no longer seen as a means of facilitating communication, but as an act of communication.

Ultimately, translation is just like driving; the driver does not solely look at what is right in front of them, but at what is up ahead.