Outbreaks at meat packing plants, health disparities mean disease is hitting immigrants hard.

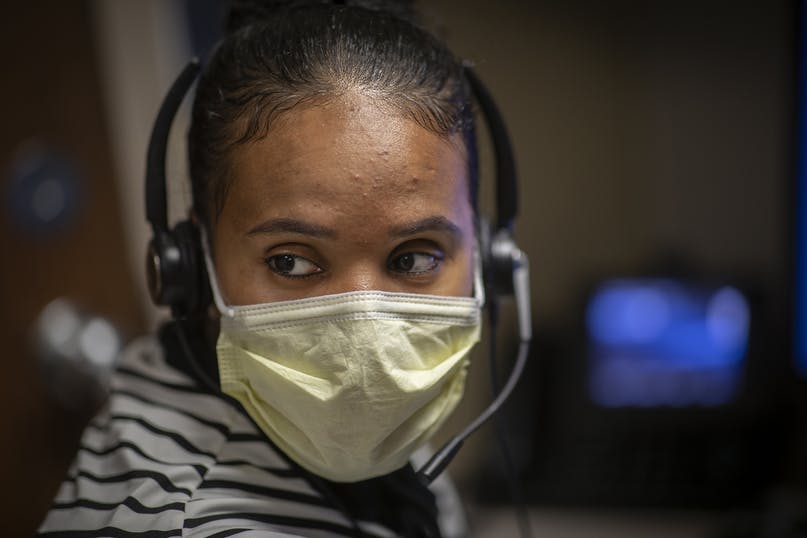

The pandemic has heightened the need for interpreters as hospitals cope with a disproportionate number of COVID-19 patients who speak languages other than English.

As of mid-May, 22% of the Minnesota Department of Health’s interviews with people who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases required an interpreter — more than five times the proportion of the state’s population lacking fluency in English.

At least part of the trend is driven by outbreaks at meatpacking plants that employ many immigrant workers, such as the JBS pork processing plant in Worthington, where hundreds of employees contracted the virus.

But the health department and major health care organizations had no explanation for why the number is so much higher than the roughly 4% of the state’s population who reported to the U.S. Census Bureau that they speak English “less than well.”

“In general, health disparities have really come to the surface with COVID-19,” said Idolly Oliva, director of language services at the M Health Fairview health care services provider in Minneapolis. “More than ever, language services are crucial to control the pandemic.”

When the pandemic hit, M Health Fairview shifted its 60 staff interpreters to call centers to communicate with patients remotely as in-person interactions grew risky. Medical staff contact interpreters over iPads mounted on a cart with wheels — dubbed an “interpreter on a stick” — and conference phone devices. When videoconferencing is not possible, the system shifts to audio.

On a daily basis, 30 to 40% of M Health Fairview’s COVID-19 patients have needed an interpreter, a spokesperson said. In-house interpreters work in 16 languages, with Karen and Somali being the top non-English languages related to COVID-19 cases.

Oliva said M Health Fairview has worked with researchers around the U.S. to help interpreters explain medical terms in some languages. Some are newer languages with more limited vocabularies and speakers may come from countries with different health care systems, she said. Interpreters also work with providers to help them rephrase or ask more open-ended questions that fit a patient’s culture.

“Coming myself from a family that doesn’t speak the language, I can tell you that when you see someone on the screen that may look like you, is from your community and can speak your language, that really brings such a touching moment for the patient,” said Oliva, whose first language is Spanish.

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) interviews with COVID-19 patients spanned 27 languages other than English. A majority of them took place in Spanish and Somali, 57% and 28%, respectively. Karen accounted for 5%, Amharic 2%, and all other languages 8%. Those numbers don’t include people interviewed for contact tracing, said Julie Bartkey, an MDH spokeswoman. And she noted that not all those who tested positive for the coronavirus have been interviewed yet.

Health department epidemiologist Mateo Frumholtz said that early COVID-19 cases were predominantly English-speakers; then came a wave of Spanish-speaking patients. Frumholtz shifted to working full time to interview people in Spanish and sought other bilingual employees to do the same. The agency — like many hospitals — used the Language Line service for on-call interpreters in less widely spoken languages. But as the numbers grew, particularly as meatpacking plant cases surged, the agency contracted with interpreters to help.

“We were getting a little overwhelmed, but … we’ve quickly increased our capacity,” said Frumholtz, who is the agency’s leader for case investigations involving non-English speakers.

In Worthington, where hundreds of JBS meatpacking workers tested positive, Sanford Health was accustomed to managing care for an ethnically diverse population. The plant alone has workers that speak more than 56 languages. But as health care services unrelated to COVID-19 were put on hold, Sanford Worthington allowed three bilingual employees to avoid layoffs and instead be trained as interpreters to help with the influx of immigrant patients sickened by the novel coronavirus.

Most of Sanford Worthington’s interpreting services are still contracted out. Though the organization prefers in-person interpreters, it’s had to rely on videoconferencing for COVID-19 patients who speak rarer languages and dialects. Multilingual access extends to Sanford’s drive-through testing site, where an interpreter is available for people who call ahead to a nurse triage line for an appointment. Sanford has emphasized the importance of everyone coming in.

“I think for everybody there’s some hesitancy of how sick am I? Do I really need to go in?” said Jennifer Weg, executive director of Sanford Worthington. “I know that’s universal for all cultures, but we really had … to make sure that those of diverse cultures know that we want them to come in and seek care.”

Eh Tah Khu, executive director of the Karen Organization of Minnesota, said he believes the virus spread in the Karen community as meatpacking workers went home and exposed their families. He also suspects there are delays in getting out information translated into Karen, which is a newer language in Minnesota than Somali or Spanish.

Some refugees he knows haven’t yet recognized the severity of the virus.

“I feel like, for whatever reason, a lot of people are not taking this very seriously,” Khu said. “I keep hearing some of the people keep saying it is just kind of a different flu.”

As outbreaks at meat-processing plants also made the St. Cloud area a COVID-19 hot spot, CentraCare Health reached out to immigrant and refugee communities in their respective languages. For example, it has worked with the local Somali radio station to share information on COVID-19 and deployed people like Hani Jacobson to be a community liaison of sorts. Jacobson and her team field calls for assistance from Somali-Americans and help connect them with other services when needed.

Jacobson believes the virus spread disproportionately among Somali-Americans because many had essential jobs in warehouses and meatpacking plants, where they worked closely together and were exposed to the virus and then brought it home to families living in close quarters. Jacobson noted that Somalis, with their large networks of family, neighbors and friends, often share vehicles or depend on one another for rides, making it harder to self-isolate.

“When you still have people working in places that they’re exposed to the virus and they come back to their tightknit, tight-space communities, that’s like a breeding ground for a virus,” said Jacobson, a registered nurse and community health specialist. “For this community, they had all odds against them.”

Jacobson said some fear being stigmatized if they share their diagnosis. She wonders how interpreters can explain to someone with language and cultural barriers “something that’s so new that even us professionals are still wrapping our heads around it?”

“We just have to take our time, and sometimes I talk to the same person for two hours trying to help and make sure they understand,” she said.