BY PHILISSA CRAMER AND JOE BAUR, Jewish Telegraphic Agency

When Lazarus Goldschmidt completed his translation of the Talmud into German, the world he had hoped to serve when he started 40 years earlier was in the process of being destroyed.

It was 1935, two years after Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany, and Goldschmidt himself had already fled to London. Over the next decade, virtually every Jew in Germany either escaped or was murdered. Goldschmidt’s feat — he was the first to complete a full translation of the Talmud into any European language — was recognized, but his work had little practical impact.

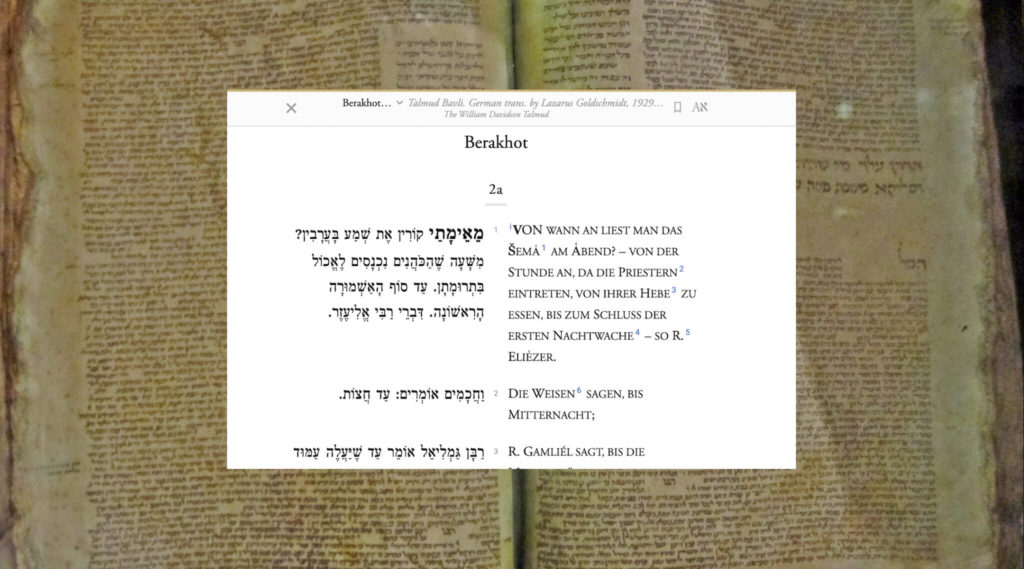

Now, nearly 90 years later, German-speaking Jews are getting another chance to engage with Goldschmidt’s work. Sefaria, the website that makes Jewish texts available and interactive online, has added Goldschmidt’s translation to its library.

“The original publication of this document was a milestone event in German Jewish life,” said Igor Itkin, a German rabbinical student who led the team that adapted Goldschmidt’s translation for online use, in a statement released by Sefaria. “Making it available online not only preserves that legacy, but also introduces it to future generations.”

Itkin told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that he has already heard from Germans who have begun using the translation in their study of Daf Yomi, the daily page of Talmud that Jews around the world learn in unison. “The response has been very positive,” he said.

Scholars of Judaism in Germany have sought to make Jewish texts available in German for decades, but the Talmud translation project gained steam after Itkin and his colleagues, German and Austrian scholars, took on the project after he realized that Goldschmidt’s work would enter the public domain at the beginning of this year.

It took them five months for the team to make its way through the 9,434 pages of Goldschmidt’s translation, reviewing and correcting errors in the scanned version and formatting it so users can navigate among the German, English and Hebrew/Aramaic translations that Sefaria makes available. (Sefaria’s CEO, Daniel Septimus, is a board member of 70 Faces Media, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s parent company.)

The translation will be the subject of an online event Oct. 24 featuring scholars who will speak to its significance. But it already took center stage once, premiering earlier this month in Berlin as part of this year’s “Festival of Resilience,” a series of events celebrating how German Jewish communities have persisted in the face of hate.

“It was very important to us to do an event in German, because this is a tool for a German-speaking audience,” said Rabbi Jeremy Borovitz, director of Jewish learning for Hillel Deutschland, who helped coordinate between Itkin’s team and Sefaria. “There’s a lot of excitement from German rabbis because finally, it’s opened up a way that they can really bring Talmud learning to their audiences.”

The translation’s accessibility comes amid surging interest in Jewish studies at German universities as well as in less formal settings. Sefaria’s tools allow users to draw from its library to create source sheets, or Jewish study texts, meaning that individual classes and communities will be able to tailor the new materials for their needs.

The digital German Talmud represents “a way of making important Jewish texts available and accessible for a new generation of German-speaking Jews who are eager to learn and explore what it means to be Jewish today,” Katharina Hadassah Wendl, an Austrian student at the London School of Jewish Studies who assisted with the project, told JTA.

She added, “For me personally, this project has opened my eyes anew to the depths of Torah and the vast sea of Talmudic discussions and wisdom.”

Joshua Foer, an author and cofounder of Sefaria, said in a statement that the translation’s online release represents the triumph of Jewish tradition over the forces of hate that lapped against Goldschmidt as he worked.

“Goldschmidt released the translation at a time of rising antisemitism to dispel dangerous myths and make the text accessible to all German speakers around the world,” Foer said. He added, “That this translation is being made more accessible today with the help of German and Austrian rabbinic students and scholars representing the future of German Judaism is a fitting celebration of Goldschmidt’s legacy.”

Goldschmidt died in 1950 shortly after the Royal Library in Copenhagen acquired his collected works and papers. His other contributions included the first German translation of the Quran and a parody commentary on creation that he published under the moniker Arzelai bar Bargelai.

Sefaria is in the process of adding French and English translations of the Jerusalem Talmud, an alternate form of the foundational Jewish text, that also recently entered the public domain. And with their work on Goldschmidt’s Talmud complete, Itkin and his team will get to work on translating other texts, such as the Mishnah, with commentary from prewar German rabbis including David Zvi Hoffmann and Eduard Baneth.

One day, they hope that text and others will appear on Sefaria in German as well, ready to engage German students and synagogue-goers in their native language.

“There’s a source of pride that the first language other than English on Sefaria is German,” said Borovitz. “It speaks to some of the resilience of this text and also this community and that it’s growing, and that people are optimistic about the future.”