If Glenview School District 34 wanted to hold a model United Nations event, it would not have to look outside its buildings’ walls to find participants with a penchant for languages spoken around the world.

With two programs focusing on a pair of languages at the school and 48 languages spoken in the homes of its students, the district has become a place to celebrate its diversity and give youngsters learning opportunities unavailable to most students on the North Shore.

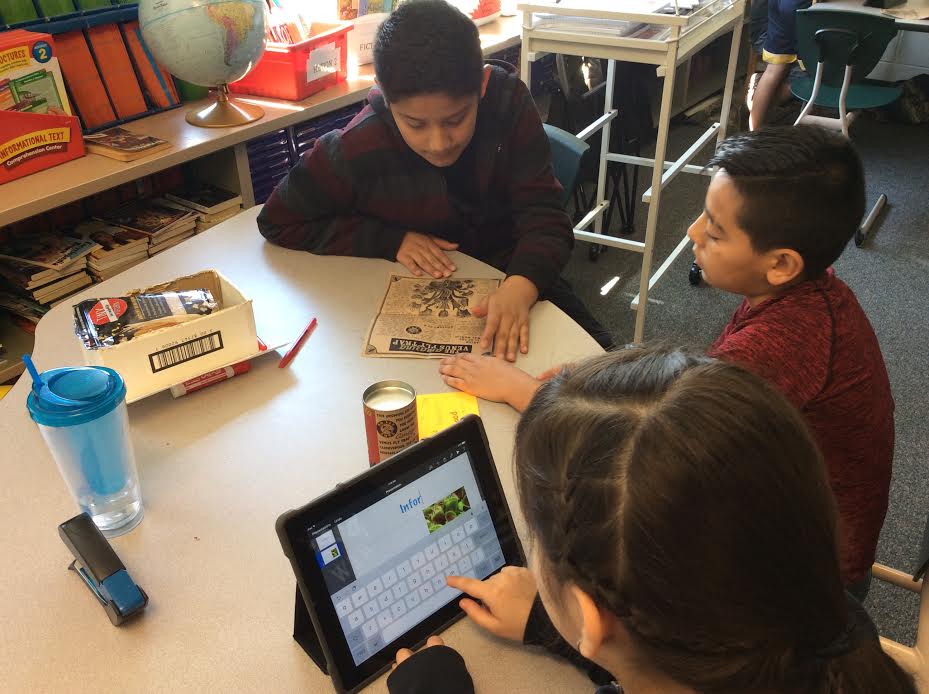

(Photo courtesy of Glenview School District 34.)

The five most common languages spoken either by the students or their parents, in order of frequency, are Spanish, Korean, Polish, Mongolian and Russian. But there are 43 others from European and Asian countries, according to Kristy Patterson, director of English learners and bilingual programs for Glenview School District 34.

“We make sure there is a celebration among everyone of our diversity,” said Patterson. “We want students to feel good about being a bilingual person.”

Irene Villa, principal at Henking Elementary School, said there are assemblies and other special days during the year where the students’ diversity is celebrated. They come in costume giving their schoolmates a taste of their culture. Henking has an international day.

“We have 12 countries represented in our school,” said Villa. “We have food, games and culture. We have performances from some of the countries showing the diversity of our school.”

While the largest percentage of multilingual students is Hispanic at 15 percent, an even larger percentage—16 percent— comprises the Asian languages of Korean, Japanese and Mongolian.

Both Henking and Hoffman Elementary schools have bilingual programs in Spanish and English. The programs start in preschool and continue through fifth grade before the students enter middle school.

At Henking the daily announcements are delivered in English and Spanish. Villa, who was once a newcomer to the United States herself, gives the daily message in both languages. She said she hopes she can be a role model to others.

“We want school to be a place of safety,” said Villa. “It’s very important for them to have someone to look up to. If they (and their parents) see someone like me than they know they can do it too.”

Students in the Korean program at Westbrook Elementary School start in kindergarten and finish at the end of second grade, according to Patterson. She said it is not as robust as the Spanish discipline because there are not enough children to mandate a full classroom in each grade.

The Korean language speakers are pulled out of their class and given special instruction during the early grades, according to Patterson.

Some of the students know the language because their parents speak it at home while others are newcomers to the country and the community, according to Patterson. The screening starts when parents register students for school.

Patterson said each registration form ask what languages are spoken in the home other than English. Once that is known, the child is tested for English proficiency. Those results determine if the youngster is placed in an English language only classroom, a dual language room or gets some other form of help.

Some students arrive in school with little or no knowledge of English while others are a step away from fluent and others speak both their native language and English equally well, according to Patterson.

Patterson said if necessary, the district finds a way to translate into each of the 48 languages either with the services of a person in the district who is fluent, an interpreter or a translation service.