For Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, translating together extended naturally from their relationship as husband and wife. Now, it is their life’s work.

By Joshua Barone, The New York Times

The first time Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky translated a Russian novel together, it felt as though another man had joined their marriage: Dostoyevsky.

“It was a mariage à trois,” Volokhonsky said over coffee at her and Pevear’s rambling apartment in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. “Dostoyevsky was always in our mind. We just lived with him.”

They were, Pevear recalled, pouring themselves into “The Brothers Karamazov,” Dostoyevsky’s immense final novel. “Well,” Volokhonsky said, “at least we like each other.”

Their translation of “The Brothers Karamazov,” published in 1990, was so well received that a full-page review in The New York Times Book Review declared, “The truth is out at last.” Their edition of the novel, it continued, “finally gets the musical whole of Dostoyevsky’s original.”

Since then, Pevear and Volokhonsky, he now 81 and she 78, have become reigning translators of Russian literature, publishing an average of one volume per year, including classics by Tolstoy and Chekhov, as well as lesser-known books and works by contemporary writers like the Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich. In their reach, the couple are the Constance Garnett of our time, making vast swaths of Russia’s written word available to the West, for which they have received both adulation and full-throated condemnation.

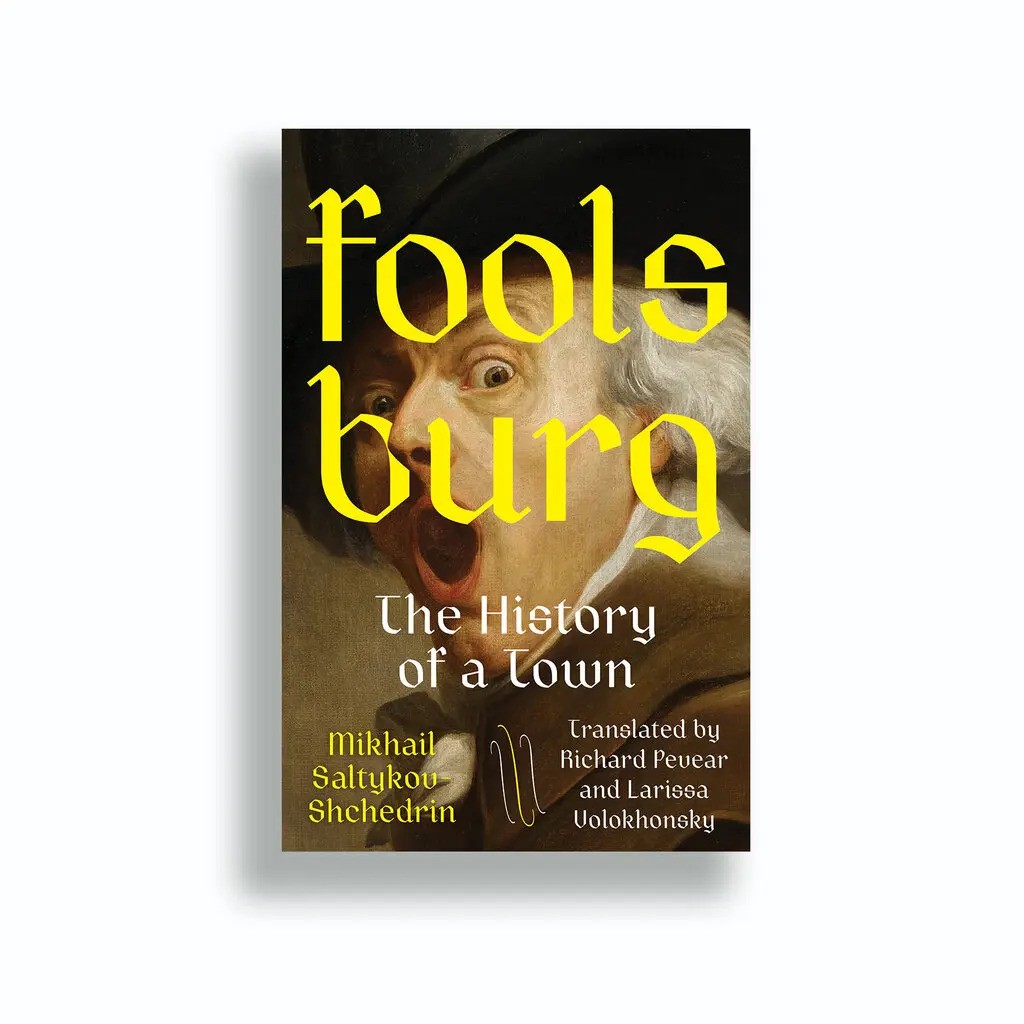

Their latest project is a translation of Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin’s “Foolsburg: The History of a Town,” published earlier this month by Vintage. To Anglophone readers, to whom the book is largely unknown, it will be a corrective to the only previous translation available, from 1980, as well as an argument for the book’s Swiftian wit and its relevance to Russia and the United States today. There is even a character in it named Trump.

In Russia, “The History of a Town” is read in schools and regarded as a masterpiece of 19th-century satire that skewered the country’s leaders and commoners alike through a clinically straightforward chronicle of a place called Foolsburg. “Stupidity, thievery, deceit, skulduggery — whatever you want to name, it’s there,” Pevear said.

But the previous English translation still in print, by Paul Foote, who died in 2011, is insistently literal, missing the wordplay that makes the book so funny; names, for example, are left in Russian, meaningless to people who don’t speak the language. That is the biggest change in the often wry, even laugh-out-loud version by Pevear and Volokhonsky. Foote’s Baklan has become Blockheadov; Borodavkin, Wartbeardin; Pryshch, Pustule; and so on. Even the name of the town, in Foote’s edition, went untranslated as Glupov, instead of as Foolsburg.

There is a Putinesque leader of the town who dreams of restoring Russia’s former glory by returning “ancient Byzantium under the sway of the Russian state.” Late in the book, Saltykov introduces a character named Trump (an exact translation of Kozyr), a “simple ragpicker” who takes advantage of crisis to make money and switches from one party to another for political gain. He is so careful about covering his tracks that when he is finally brought under real scrutiny, he is found not guilty and deemed “truly the worthiest citizen, who greatly contributed to the suppression of the revolution.”

Volokhonsky called the book “timeless,” adding that, “it’s very much bound with Russian history, but it’s also about the human condition.”

She and Pevear translated “The History of a Town” using virtually the same method as for “The Brothers Karamazov.” They have been together for 42 years, and have collaborated for nearly as long, brought together, they said, seemingly by fate.

Pevear, an American writer who maintained working-class jobs in places like a New England boat yard, had published an article that caught the attention of a Russian professor named Irina Kirk. She wanted to introduce him to a friend of hers who had emigrated from the Soviet Union: Larissa Volokhonsky, who, while a graduate student in Leningrad (modern-day Saint Petersburg) in 1973, had impulsively moved to the United States by way of Italy.

Volokhonsky, a linguist by training, had enrolled at Yale Divinity School. Pevear, who was living in New York at the time, went up to Connecticut to meet her, not knowing that she was actually in his city renewing her visa. “It was like Nabokov,” Volokhonsky said with a laugh.

They eventually met in Connecticut, and when Volokhonsky moved to New York, it was to an apartment across the street from Pevear’s building. It wasn’t long before they were living together. Then, when she saw that he was reading David Magarshack’s translation of “The Brothers Karamazov,” she decided to join him, reading the original in Russian. Sometimes, out of curiosity, she would ask how a seemingly idiosyncratic phrase was translated, only to find out that it wasn’t.

“Suddenly, a light went on,” Volokhonsky said. “We decided that we would translate it.”

She created a word-for-word, phrase-for-phrase translation into English that Pevear, who doesn’t speak fluent Russian, then smoothed over. She took that back to the original text and questioned some of his changes; they discussed the entire manuscript, she said, and, setting a precedent that continues today, disagreed without ever fighting. (Like any couple, they bicker instead about everyday things around the home. When, during the visit to their apartment, he asked her whether he was in her way, she responded, “Yes, you are always in my way.”)

Before sending their translation to the publisher, Pevear read it aloud while Volokhonsky followed along with the original book. The goal, they agreed, was simple: to do in English what Dostoyevsky did in Russian, as opposed to, Pevear said, “imposing English rules on Russian.”

It wasn’t easy to get “The Brothers Karamazov” published. They had initially been offered a $1,000 advance, which they were able to negotiate to $6,000. But it was a $36,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that made the translation possible. With two young children, they moved to Paris, quit outside work and finished the job.

The translation was well received, but a follow-up wasn’t necessarily a given. They signed a contract for three additional Dostoyevsky books, which sold well, then moved on to Nikolai Gogol, which didn’t. They worked in their Paris apartment, in separate rooms but within shouting distance, so they could communicate. Eventually, they made their way to Tolstoy, with, for example, a version of “Anna Karenina” that restored the writer’s rhetorical repetition of words, like “enchanting” to describe the title character.

Along the way, they established certain red lines. They didn’t translate Russian dramas until they started to collaborate with the Chekhov-esque playwright Richard Nelson. They still don’t translate poetry. “Too much gets lost,” Volokhonsky said. “When Pushkin translated Dante and Shakespeare, it was Pushkin’s poetry, inspired by them. We were asked to translate Pushkin, but it’s impossible. There are amazing ‘Onegin’ translations, but they are not Pushkin.”

A bit of good luck arrived in 2004, when their “Anna Karenina” was selected for Oprah’s Book Club, an anointment that flipped the fortunes of a commercially modest translation. From the outside, Volokhonsky said, it looked as though she and Pevear had been raised “out of abject poverty to enormous riches.” In reality, they finally had a pension fund and an accountant.

Still, they became targets of criticism that they were rampaging through Russian literature as if it were a trove of treasures more literal than figurative. Janet Malcolm, in a scathing essay in The New York Review of Books, accused them of establishing “an industry of taking everything they can get their hands on written in Russian.” The scholarly critic Gary Saul Morson also wrote a takedown, called “The Pevearsion of Russian Literature,” in which he wrote that their works are “Potemkin translations — apparently definitive but actually flat and fake on closer inspection.”

Pevear and Volokhonsky had their defenders, and there were holes in attacks against them. Neither Malcolm nor another harsh critic, Helen Andrews, spoke Russian, for example; they just preferred Garnett’s Edwardian translations and seemed to dislike modern translations in general.

In a response to Malcolm’s essay, the author and translator Alice Sedgwick Wohl wrote that she preferred Pevear and Volokhonsky’s translations “because I always sense the presence of the original behind the window. I also love Garnett’s translations, for all the reasons that Janet Malcolm adduces, although I always feel I am reading an English novel set in Russia.”

Ultimately, how Pevear and Volokhonsky’s translations are viewed depends on a reader’s philosophy of the craft. Garnett’s are eloquently of their time but have been seen by some as infelicitous oversteps that transformed Russian more than translated it. Pevear and Volokhonsky aim for something like objectivity and fidelity; if the diction sounds awkward, it’s a reflection of the author’s stylistic quirks, not their own.

“We don’t try to be different,” Volokhonsky said. “It just comes out different. It’s nice to be praised, and it’s bad to be criticized, and Garnett was a great woman. We just translate differently. People can prefer her translations or ours, and that’s fine. People have different tastes.”

Joshua Barone is the assistant classical music and dance editor on the Culture Desk and a contributing classical music critic. More about Joshua Barone